Data citations and data availability statements#

Most students and researchers have been trained to cite their sources. Mostly, this is meant to be literature sources, but the basic idea applies just as much to data: If you use somebody else’s data, you should acknowledge that.

Note

See the relevant presentation slides.

A very short history of data citations#

The almost complete absence of data citations from the literature has lead to issues when data creators and data providers attempt to assess their impact on science. Typically, they revert to manually or algorithmically scouring the literature, trying to find instances where their data is used.

In 2016, a number of scientists and publishers from many domains got together and issued the FAIR Data principles [FORCE11, 2016]. “FAIR” is an acronym for

Findable,

Accessible,

Interoperable, and

Re-usable

These are principles which help the furthering of increased reproducibility - by making data accessible, reproducibility checks can be conducted. By making them interoperable and re-usable, others can reproduce, replicate, and expand on the original research. Findability remains an issue: how do you discover data that is hidden in a ZIP file on a journal website as part of an (otherwise) perfectly reproducible package?

In fact, the same group had previously laid the groundwork to that. In 2014, they issued the “Data Citation Principles (DCP)” [Martone, 2014]. These laid out the ethical need for such citations, the content such citations should have, and some desirable attributes of data citations. Both the DCP as well as FAIR suggest that data be assigned unique identifiers, allowing them to be clearly referenced, and found. The most common identifier in the social sciences is the Digital Object Identifier (DOI), but others exist, in particular in the biological or physical sciences.

The DCC note that (emphasis added):

Sound, reproducible scholarship rests upon a foundation of robust, accessible data. For this to be so in practice as well as theory, data must be accorded due importance in the practice of scholarship and in the enduring scholarly record. In other words, data should be considered legitimate, citable products of research. Data citation, like the citation of other evidence and sources, is good research practice and is part of the scholarly ecosystem supporting data reuse.

Data citation increases the findability, accessibility, interoperability, and re-usability of research data (FAIR). Through data citations, data providers can link to articles (sometimes automatically), allowing them to show the academic value of the data and continue providing the services around data creation. Finally, data citations open a new path to finding relevant science, by reaching the linked articles through data search interfaces, like openICPSR, Data-Pass, and Google Dataset Search.

These principles are imperfectly implemented even today. Many data providers, including some of the biggest statistical agencies, do not provide unique identifiers to a particular data file. Some might uniquely identify a data series. Others may heuristically refer to certain versions (“V2”). Few have robust archival quality unique identifiers.

Journals’ stylistic considerations also reduce the impact of the DCC. Citations - in the sense of appearing in a bibliography at the end of the document - do not provide much sense of any access method other than a download. The AEA follows the Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS), with several additions on the AEA website.

As the CMOS states, one of the criteria for a useful citation is conveying authority and permanence:

Electronic content presented without formal ties to a publisher or sponsoring body has the authority equivalent to that of unpublished or self-published material in other media.

FAIR data helps convey such information, but often, assessing what “publisher” or “sponsoring body” is reputable or reliable is tricky. And the citation fails to convey many important facets of data access. What if the cited resource requires a login, even if it is free? What if payment is required? What if a long-winding application process is required? Citations do not communicate that amount of detail. As we shall see later, there are ways to augment data citations with the needed information.

How do you create a data citation#

ICPSR [ICPSR, n.d.] notes that a citation should include the following items:

Author

Title

Distributor

Date

Version

Persistent identifier

where any data source has the first five elements, and the ideal FAIR curated data source also has a persistent identifier.

An imperfect real example#

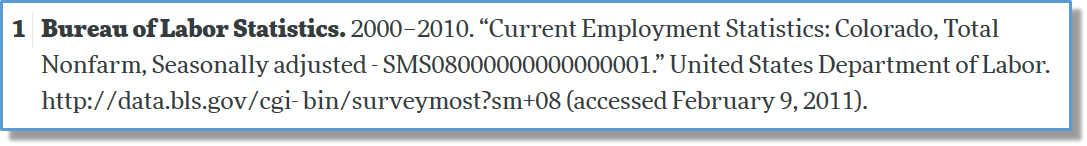

Consider the BLS citation shown earlier:

Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2000–2010. “Current Employment Statistics: Colorado, Total Nonfarm, Seasonally adjusted - SMS08000000000000001.” United States Department of Labor. http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/surveymost?sm+08 (accessed February 9, 2011).

The author or creator is clearly Bureau of Labor Statistics. The distributor here is United States Department of Labor, which happens to be the government department housing the BLS. Title is arguably Current Employment Statistics: Colorado, Total Nonfarm, Seasonally adjusted, though some might argue that state, coverage, and seasonal adjustment identify versions of the survey. Date are the (original) dates of publication, or here, approximated by the date range covered by the series. But generally, versions relates to a chronologically released version - which is less clear in this case, and only captured by (accessed February 9, 2011). There is no clear persistent identifier, the closest approximation is provided by a combination of the series identifier SMS08000000000000001, the URL http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/surveymost?sm+08, and the date accessed (accessed February 9, 2011). Note that this is imperfect, because, unless you can time-travel, you cannot obtain the same dataset a second time.

Attribute |

Value |

|---|---|

Author: |

|

Title: |

|

Distributor: |

|

Date: |

2000-2010 |

Version: |

|

Persistent identifier: |

|

An ideal (?) data citation#

What should the ideal data citation look like? ICPSR suggests

Barnes, Samuel H. Italian Mass Election Survey, 1968. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 1992-02-16. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR07953.v1

so that

Attribute |

Value |

|---|---|

Author: |

|

Title: |

|

Distributor: |

|

Date: |

|

Version: |

|

Persistent identifier: |

|

Note that the date 1968 describes the survey, but its date of publication was 1992. The version is implicit in the DOI. The persistent identifier is just 10.3886/ICPSR07953.v1, but the display guidelines for DOI suggest including the full URL that yields a resolution.

Data citation template#

In general, therefore, as long as you can fill out the table

Attribute |

Value |

|---|---|

Author: |

|

Title: |

|

Distributor: |

|

Date: |

|

Version: |

|

Persistent identifier: |

you can create a data citation:

[AUTHOR], “[TITLE]”, [DISTRIBUTOR], [DATE], [VERSION] + [Persistent Identifier]

A not quite serious example#

Many authors initially neglect to add data citations, or do not know how to add a data citation. Often, we see authors cite papers with supplementary data, but not databases or other data:

We use data acquired from the NHL, dates of power outages collected by Tremblay et al (2018), augmented with information on the language and grammar skills of hockey players provided by the Ethnologue database.

(note absence of citation for NHL and Ethnologue data). In the above example, three datasets are used, but only one is cited in some fashion.

Better#

The above example can be improved as follows:

We use data acquired from the NHL (NHL, 2018), dates of power outages collected by Tremblay et al (2018, 2019), augmented with information on the language and grammar skills of hockey players provided by the Ethnologue database (Eberhard et al, 2019).

with the reference list having the following entries:

Eberhard, David M., Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig (eds.). 2019. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Twenty-second edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com.

National Hockey League. 2018. NHL Game Database 1917-2018. National Hockey League Hall of Fame, Toronto, ON. Accessed February 29, 2019.

Tremblay, Réjean, Ken Dryden, and José Theodore. 2018. “The impact of power outages on goal-keeping in the NHL”, Journal of National Hockey Leagues, vol 32, iss. 1.

Tremblay, Réjean, Ken Dryden, and José Theodore. 2019. “Power outages during NHL games (updated)”, Canadian Hockey Dataverse, doi:10.1234/nhl.lnh.haha

Assess why the latter is better.

Data distributed as supplementary data#

The CMOS provides examples of how to cite supplementary materials that are attached to a specific article:

Suárez-Rodríguez, M. and C. Macías Garcia. 2014. “There Is No Such a Thing as a Free Cigarette: Lining Nests with Discarded Butts Brings Short-Term Benefits, but Causes Toxic Damage.” Journal of Evolutionary Biology 27, no. 12 (December 2014): 2719–26, https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12531, data deposited at Dryad Digital Repository, https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.4t5rt.

The AEA guidance used to provide an example, in which the citation links to the article landing page:

Romer, Christina D., and David H. Romer. 2010. “The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes: Estimates Based on a New Measure of Fiscal Shocks: Dataset.” American Economic Review. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.3.763.

Many authors, however, would only cite the article itself, and not the data. Note however that modern data citation guidance suggest that both the article and the data used by the article should be cited, and this can lead to confusion. With the 2019 move of the AEA to a data archive, the correct citation for the above supplement would be:

Romer, Christina D., and David H. Romer. 2010. “Replication data for: The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes: Estimates Based on a New Measure of Fiscal Shocks.” American Economic Association [publisher], Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], https://doi.org/10.3886/E112357V1

with the article also cited as:

Romer, Christina D., and David H. Romer. 2010. “The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes: Estimates Based on a New Measure of Fiscal Shocks” American Economic Review. no. 3 (June 2010): 763–801. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.3.763.

Producer#

Often, the creator of a dataset is an organization. The same way that an organization as a work’s author can be cited:

ISO (International Organization for Standardization). 1997. Information and Documentation—Rules for the Abbreviation of Title Words and Titles of Publications. ISO 4:1997. Paris: ISO.

an organization can be cited as the creator of a dataset:

Standard and Poor’s (S&P). 2017. Compustat-Capital IQ. S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Distributor#

In many cases, the data are not distributed by the creator. This means the distributor takes on the role of a publisher (of a book, of data). In the BLS example, the two differed only because the (higher-ranking) department counts as the distributor. In the case of Compustat, one might have obtained access through the Wharton Research Data Services, and cite as

Standard and Poor’s (S&P). 2017. Compustat-Capital IQ. Wharton Research Data Services. https://wrds-www.wharton.upenn.edu/pages/about/data-vendors/sp-global-market-intelligence/

If using the S&P 500 data, there may be multiple providers:

S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, S&P 500 [SP500], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/SP500, January 24, 2020.

S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, S&P 500, provided via Haver Analytics Data Subscription, February 24, 2018.

with hopefully the same content. Note that often, such data is subject to copyright and redistribution restrictions (see the page at FRED on SP500 and discussion in the later section).

Dates#

In some cases, it isn’t clear when the dataset was published, though it may be clear what time period the dataset covers (as in the BLS case). One way to address this may be by using the “n.d.” abbreviation for the date of publication and including the date of coverage in the title:

Standard and Poor’s (S&P). n.d. Compustat-Capital IQ (1982-2017). Wharton Research Data Services. Accessed April 6, 2018. https://wrds-www.wharton.upenn.edu/pages/about/data-vendors/sp-global-market-intelligence/

A related issue may arise when the dataset is comprised of multiple years, each of which has its own DOI. For instance, when accessing multiple years of American Community Survey data on ICPSR, each has its own DOI:

American Community Survey (ACS): Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS), |

1998 |

(ICPSR 3888) |

2008-05-21 |

American Community Survey (ACS): Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS), |

1997 |

(ICPSR 3886) |

2008-05-21 |

American Community Survey (ACS): Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS), |

2003 |

(ICPSR 4117) |

2009-12-01 |

American Community Survey (ACS): Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS), |

2004 |

(ICPSR 4370) |

2008-10-14 |

American Community Survey (ACS): Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS), |

2009 |

(ICPSR 33802) |

2013-04-04 |

American Community Survey (ACS): Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS), |

2008 |

(ICPSR 29263) |

2011-11-08 |

One approach to this is to create a composite citation, with additional information available in an online data appendix or a Data Availability Statement:

Bureau Of The Census. 2009. “American Community Survey (ACS): Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS), 1997-2009.” United States Department Of Commerce [publisher]. ICPSR - Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research. [distributor] DOIs listed in data appendix.

or

Bureau Of The Census. 2009. “American Community Survey (ACS): Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS), 1997-2009.” United States Department Of Commerce [publisher]. ICPSR - Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research. [distributor] https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/search/studies?q=american+community+survey (accessed November 21, 2019)

(and listing of exact DOIs in an appendix table).

Offline access mechanism#

Many datasets are available only under license, memorandum, contract, etc., and do not have a formal online presence. This is quite similar to traditional offline archives, for instance manuscript collections. For such collections, CMOS suggests:

Kallen, Horace. Papers. YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York. Merriam, Charles E. Papers. Special Collections Research Center, box 26, folder 17. University of Chicago Library.

and usage in the text as

Alvin Johnson, in a memorandum prepared sometime in 1937 (Kallen Papers, file 36), observed that …

Similar citations can be constructed for offline databases:

Bloom, Nick. 2019. Confidential survey data on Cameroon business processes. Stanford Secure Access Center (file “cameroon-bloom.zip”). Stanford University.

Confidential databases#

Similar forms may be used for confidential databases when no DOI exists:

Internal Revenue Service. (YEAR). Corporate Income Tax Returns [database]. Department of Treasury, Washington DC, accessed YYYY-MM-DD.

where the data, in this case, were accessed via the “Department of Treasury,” acting as a secure distributor (of access, not downloads). If the same data had been accessed via a secure research data center, the reference should have instead noted that access mechanism:

Internal Revenue Service. (YEAR). Corporate Income Tax Returns [database]. Federal Research Data Centers, last accessed YYYY-MM-DD.

Confidential data with DOI#

If a DOI exists, of course, the formal citation generated from that DOI should be used:

Forschungsdatenzentrum der Bundesagentur für Arbeit. 2020. “Betriebs-Historik-Panel (BHP) – Version 7518 v1.” Institut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung (IAB). https://doi.org/10.5164/IAB.BHP7518.DE.EN.V1.

No formal access mechanism#

In some cases (not infrequently), access to data is through informal means. The CMOS allows for citation of such information, without inclusion in the references.

(A. P. Møller, unpublished data; C. R. Brown and M. B. Brown, unpublished data)

We would deviate from that suggestion, ask for inclusion in the reference list, and simply suggest using unpublished data as the locator, similar to a URN, in the reference list:

Møller, A. P. n.d. “Data on Crocodile Sightings in Manhattan.” unpublished data. Accessed February 29, 2019.

Where to cite#

In all cases, data and code should be cited in the main manuscript. They should also be referenced in the data availability statement (some journals) or the README (other journals). However, in some cases, data is only used in an online appendix, and it is acceptable to cite the data there as well, and not in the main manuscript’s bibliography.

Furthermore, as data citation are still a relatively new concept, many authors will have substantially completed their manuscript, without including data citations. Adding them to the README is then acceptable practice (for now).

Data availability statements#

The academic publishing community’s response are “data availability statements (DAS).” While mostly, these are pointers from the journal to where the data can be found. In the case of data supplements, this is almost trivial when the journal has a robust data availability policy, though some journals allow for self-declared but unverified DAS.

Summarily, a data availability statement describes not just where the data can be obtained from, but also how the data can be obtained, conditions for obtaining it, and any additional restrictions.

Some examples of DAS#

Example for public use data included in data archive:#

The paper uses data obtained from IPUMS (Ruggles et al, 2017). IPUMS-CPS does not currently provide the ability to store or reference custom extracts, but allows for redistribution for the purpose of replication. The archive contains the extracted data, codebook in the folder “data/IPUMS”. The data citation in the main article has the full URL.

Example for public use data not included in data archive:#

Data from the Socioeconomic High-resolution Rural Urban Geographic Dataset on India, Version 1.0 (Asher and Novosad, 2019) is used in this paper. The full dataset and documentation can be downloaded from https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DPESAK.

Example for public use data with required permission:#

The paper uses IPUMS Terra data. IPUMS-Terra does not allow for redistribution, except for the purpose of replication archives. Permissions as per https://terra.ipums.org/citation have been obtained, and are documented within the “data/IPUMS-terra” folder.

Example for confidential data:#

The data for this project are confidential, but may be obtained with Data Use Agreements with the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE). Researchers interested in access to the data may contact [NAME] at [EMAIL], also see www.doe.mass.edu/research/contact.html. It can take some months to negotiate data use agreements and gain access to the data. The author will assist with any reasonable replication attempts for two years following publication.

Example for Government registers#

In some cases, governments have a list of their (named) registers. For instance, Statistics Denmark provides the full list of registers at http://www.dst.dk/extranet/forskningvariabellister/Oversigt%20over%20registre.html. These can be used to craft data citations (see Data citation guidance). Data availability statements should describe how each such register can be accessed:

The information used in the analysis combines several Danish administrative registers (as described in the paper). The data use is subject to the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation(GDPR) per new Danish regulations from May 2018. The data are physically stored on computers at Statistics Denmark and, due to security considerations, the data may not be transferred to computers outside Statistics Denmark. Researchers interested in obtaining access to the register data employed in this paper are required to submit a written application to gain approval from Statistics Denmark. The application must include a detailed description of the proposed project, its purpose, and its social contribution, as well as a description of the required datasets, variables, and analysis population. Applications can be submitted by researchers who are affiliated with Danish institutions accepted by Statistics Denmark, or by researchers outside of Denmark who collaborate with researchers affiliated with these institutions.

(Example taken from Fadlon and Nielsen, 2020 (forthcoming as of June 2020).

S&P 500#

The S&P 500 is one of the most widely known stock indexes. And yet, it is subject to copyright, and restrictions on redistribution. Some authors who use the S&P 500 numbers may have downloaded it via FRED https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/SP500, others through other data services (Haver Analytics, Bloomberg). The FRED website mentions that the data are

(C) S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC. Reproduction of S&P 500 in any form is prohibited except with the prior written permission of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC (“S&P”).

If obtained through FRED, the suggested citation is

S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, S&P 500 [SP500], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/SP500, January 24, 2020.

An analogue if accessing it through, say, Haver Analytics, might be

S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, S&P 500, provided via Haver Analytics, January 24, 2020.

Note that both citations do not provide (complete) information on how others might obtain the data, and what restrictions are imposed on the data (unless they visit the site, or read the terms of use of, say, their Haver Analytics description). A tentative Data Availability Statement might be:

S&P 500 data is (C) S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC. Reproduction of S&P 500 in any form is prohibited except with the prior written permission of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC (“S&P”). It is thus not available as part of the replication archive. Users may access the past 10 years via FRED at https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/SP500, or purchase longer access via Haver Analytics (http://www.haver.com/databaseprofiles.html#indicators). Note that reproduction of our manuscript’s tables requires data from [YYYY]-[ZZZZ].